Of Image and Images

| Written by: | Ivor |

| Published: | May 29, 2023 |

| Event: | Sabaton: The Tour To End All Tours - Europe 2023 (Website) |

| Location: | Unibet Arena, Tallinn, Estonia |

| Organizer: | Live Nation |

|

Galleries: |

Sabaton - Unibet Arena, Tallinn, Estonia, 18.05.2023 by Ivor (38) |

I was going to cover Lordi, Babymetal, and Sabaton concert only in photos and had zero plans for writing about it. However, the way subsequent events unfolded prompted me not only to put my thoughts into words in the following essay but also mainly to focus on the importance of image, and especially on the importance of an image to the image.

Those of you who have been to concerts and have ventured close to the stage have likely seen an often present fenced-off area in front of it–an area of (dubious) privilege designated to security staff and photographers. You may also even be aware of the usually enforced three-songs-and-no-flash rule in this area–a rule which photographers are given no choice but to abide by. What you are probably less aware of is that access to this area is also often highly regulated by the preceding signing of a photo release form.

A photo release form is basically a contract that defines the rights and obligations of both parties involved. It's a fairly standard practice–especially with the bigger bands–to establish boundaries as to how the photos can be taken and where they can and cannot be used and by whom. While standard practice, it is hardly an advantageous agreement to the photographer and varies in wording and terms quite a bit. Commercialisation of said photos is usually forbidden, publication media outlets are limited, the bands often claim the free and non-compensated use of the material (especially on social media), and–in the very extreme cases–even demand that the photographer denounce the copyright. It's essentially a non-negotiable power relationship where one either accepts the terms dictated by the other or takes a hike.

If you leaf through the photo books on the high period of rock music–likely any will do, like Jim Marshall's biography Show Me the Picture, or Who Shot Rock & Roll, or London Rock: The Unseen Archive–you'll come to realise that the three-song rule was not always present. In the early days the photographers would roam around everywhere, even venturing into the backstage, and few would mind. Times were different back then as we are all well aware. You are also likely to come across the references that one of the first bands to enforce the said rule were The Rolling Stones. What at first might have been a preferential treatment of their own (or favoured) photographers soon became about something else. It became about keeping the best (or at least the better) material close and commanding the circulating visuals. More importantly, however, it put them in charge of their image.

Human culture is highly dependent on the sense of sight. It's how we obtain most of the information about the world around us. While there are other forms focusing on other senses, the predominantly Western way works through observing and looking at the world. In the times of low literacy it was primarily the visual art that carried the message. People didn't know how to read but they could understand the underlying symbolism of the (religious) visual art. Paintings–all paintings, not only the religious ones–were laden with visual symbols of and metaphors for life and death, love and infidelity, good and evil, morality and sin, etc., that were undoubtedly easier to learn than the written word. It's here that a saying "a picture is worth a thousand words" should be applied, where layers upon layers of symbolism tell a story and deliver the underlying message.

The advent of photography in the middle of the 19th century was a revolution that put reality in focus. Unlike a painting, a photograph was deemed truth. It was perceived to be a slice of reality–a notion that was highly emphasised by the soon-invented and hugely popular stereoscope, which literally taught its audiences to see receding lines and to recognise depth and perspective. By its very nature it also made photographs seem as real as reality itself. It was even suggested that because of it the travelling of the world would eventually become unnecessary–an interesting prediction that in a sense has come to life in the form of Street View about a century and a half later.

It's also worth noting that the invention of the stereoscope came at a favourable time. During the 17–18th century a form of entertainment called the "raree show" had become popular at fairs. It was essentially a box a person could look into through a magnifying glass that–with the help of objects, pictures, optical illusions, and mechanics–staged miniature scenes or plays. As such, the stereoscope was embraced as an alternate form of already popular entertainment offering a glimpse of reality that people could recognise.

While a raree show could be conceived as being an illusion, the three-dimensional photographs were probably harder to denounce, especially if it were a scene of something or someone familiar. However, a photograph is never a true representation of reality. It's about what's left outside the frame as much as what one can see in it. It's about how something is photographed as much as what is photographed. It's about the composition and the photographer's intent as much as what was in front of the camera at the time. It's as much about one's literacy in reading images and underlying symbolism as it is about the photographer's message and the ways of its delivery. It's what is in the negative as much as what's rendered in the final print (which is still true for digital workflow).

Even if one were to consider documentary or street photography as "truthful," it's hardly ever so because of the decision bias of the one operating the camera. Some form of staging still remains even when aiming for a truthful end goal. Photography is powerful not because it can show reality but because it's hard to tell when it doesn't. Looking at an image, it's vital to understand what one is being shown and, more importantly, why. With photography it's just so damn easy to fool the senses and so damn hard to tell when one is shown a lie, an untruth, or even just a part of the truth.

Thus, a photograph is a construct–not a representation of reality but an artificial version of what may or may not have been a reality at the time of capture, constructed to deliver a message. It's a tool. One who knows how to operate the tool and present a message to their liking is in charge of the narrative. One who controls the narrative has the power. It's this that scares people numb about the generative AI–not only that it can eliminate countless jobs, pass the Turing test, and become indistinguishable from the human reasoning along the way. It's the perfect illusion of the truth without any cracks that's terrifying–that ultimate control of the narrative and masses.

Ever since the beginning, photography has had a difficult time at being recognised as a form of art. Paul Strand remarked that photography became valued as art only when photographers started creatively experimenting with the medium itself and its potential for expression. Art, however, has always been to the lesser or greater degree in the service of the state and higher powers. It is the photographers' high technical skills and the ability to walk on the edges of reality and the truth that are so valuable in letting the light fall in favourable ways to mould the opinion of the public.

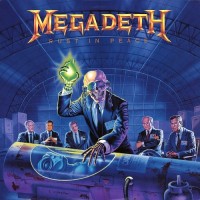

As already mentioned, our culture is dependent on the sense of sight and thus highly visual. It is so much skewed towards seeing that we don't even realise how poor are our vocabulary and verbalisation skills where sound phenomena and sound experiences are concerned. We call on metaphors and other senses to describe what we hear and feel, so much so that we don't even notice when we do that. We go to see the band live as opposed to hear it perform. We want to hear the music performed live but in actuality we require proof that it gets done. We want to see it happen in front of our own eyes. We also want albums to have cover art so that we can anchor music visually in place, and we want lyric sheets so we can see what we hear. We're interested in faces behind the names so we can feel at peace that there's someone "real" behind it all.

So it would appear that as far as music–and especially live music–is concerned we very much listen with our eyes. This is something that the entertainment industry picked up early on, this idea and that a still image can be a useful tool in constructing a visual idealised identity of an artist operating in the aural realm. The consumption of the curated circulating imagery as well as the live experience is just a process of observation of this artificial reality at a distance. Thus to be in control of the visuals is to command the image and by extension the carefully constructed reality and idea(l)s people buy into.

The three-song rule is on the one hand a tool of exercising this control. It limits who can take a picture and how and when. On the other hand–and perhaps more importantly–it's also a way to shift the power dynamic between the one who takes the photo and the one the photo is taken of. It attacks with the fundamental question: is the photographer the artist or is that the musician on stage? Perhaps it's also about setting the ground rules and enforcing the home-field advantage. While in the studio the photographer reigns, but at the concert all eyes are on stage at all times.

It brings photographers almost to the same level as the audience. One could say that the photo pit is a privilege and, admittedly, to some extent it is. However, the distance and the point of view from the pit are quite specific. In a conventional venue a raised stage is a necessity so the audience can see the performers. The closer one is to the stage, however, the more one is looking up–and it's the photographer that does it the most. While it can be viewed as another manifestation of the dominance in the relationship between the artist on stage and the photographer, the implications go further.

Photos taken from the pit often share a common trait: they–like the audience–are looking up. It seems that the shifting power dynamic has less to do with the photographer and more so with the audience. It's about setting the image of the artist apart and above the people. The image taken of the artist is in the service of the image of the artist, helping to project, uphold, and further the ideal of this constructed reality. It and–by extension–the photographer become but cogs in what appears to be a bigger scheme.

Metal, like any subculture, identifies itself through looks. Of course there's what we listen to, but short of telling one another or blasting music through open windows–in which case you're just being an ass-hat–there's little else to go by. Symbols and visual cues are as important to metal as they were to interpreting the paintings of old. The image is an inseparable part of metal music identity. Going even further, an image is the integral part of the image; in other words, to be pictured is to be seen.

The evening that sparked this train of thought featured three bands, each approaching the construction of their identity in their own way. First, there were Lordi, who wear elaborate monster costumes that they have on at all times when interacting with the public, on and off stage. By an informal agreement, photos of the members without their attire aren't normally published. The few times it has happened, at the peak of their popularity after winning the Eurovision Song Contest in 2006, seemed to turn scandalous in Finland and ended in apologies. The band are still kind of riding the wave of that win, though not much of the propelling power is left. The win, however, was far more about the idea(l) that the band represented than the music they played and play to this day. Even back then the music–much like the image they portray–was old hat and appeared novel only to those who hadn't experienced it before, giving the metal community an opportunity to make a statement.

While Lordi probably limit the photo access from inertia, the Babymetal management exerts a whole different level of control. Not only do they choose which media gets access, they also require the preview of photos intended for publication, curating carefully which of those eventually get their approval. The strict rules aren't even the interesting part of it. It's how close their scrutiny is of the photos of the girls, making sure the captured appearance corresponds to the constructed image of the band. The Japanese strive for excellence and perfection. They pay attention to the looks of the girls in order to meet the high cultural standards of the beauty ideal. After all, the illusion of perfection is easiest to uphold when no cracks are to be seen anywhere.

Finally, there were Sabaton with matching WWII lyrical themes, stage production, and attire. Contrary to what one would presume from them being the tour headliners, their photo policy was the most laidback. Not only did they give two sessions in the pit and allow photography from the floor during the rest of the show, they went to great lengths to brief on the stage production, lighting, etc. Short of giving on-stage access, they did their best to offer advice on how to capture various aspects of the elaborate performance and make sure the end result was as good as possible under the circumstances.

This varied experience leads me to conclude what I've been mulling over for quite a while: that the three-songs-and-no-flash rule is–save for the no flash part–an anachronism in this age of modern mobile devices. As a means of retaining the element of surprise about the stage show it's hardly an effective tool. Quite the opposite seems true: the more people know what to expect, the more interested they are. People buy into idea(l)s, and the abundance of visuals does more to encourage interest than withholding and being secretive can.

As a means of controlling the image of the artist, Sabaton's approach would seem to be the better one. Leaving the moneymaking discussion aside, save for the (still) better quality, more conscious composition, and purposeful curation, there is not much that sets accredited photographers' work apart and puts it in the service of furthering the constructed image of the artist on stage. Firstly, it's still the angle of the shots from up close and down below that unconsciously projects the aura of dominance. And secondly, the authority these images carry is by extension only. It's only the explicit official permission given to the photographer to be there and take these photos that renders them authoritative. They exist not because they can exist by virtue of someone's action and skill but because they are permitted to exist by virtue of someone's authority.

|

Written on 29.05.2023 by

I shoot people. Sometimes, I also write about it. And one day I'm going to start a band. We're going to be playing pun-rock. |

Comments

Comments: 6

Visited by: 106 users

| RaduP CertifiedHipster Staff |

| F3ynman Nocturnal Bro Contributor |

| ScreamingSteelUS Editor-in-Chief Admin |

| Sieva |

| Guib Thrash Talker |

| nikarg Staff |

Hits total: 2059 | This month: 36